Conditions Kidney stones and ureteral stones

ICD codes: N20 What are ICD codes?

Kidney stones form as small, solid deposits in the renal pelvis, which can move to the ureters. They often occur in people aged between 40 and 60. Larger stones can cause pain.

At a glance

- Kidney stones form as small, solid deposits in the renal pelvis.

- Sometimes the stones can move to the ureters, at which point they are referred to as ureteral stones.

- Many stones are so small that they are excreted with the urine within a few days, even without treatment.

- Larger stones can be very painful and need to be removed.

Note: The information in this article cannot and should not replace a medical consultation and must not be used for self-diagnosis or treatment.

What are kidney stones?

Kidney stones form as small, solid deposits in the renal pelvis. They may move to the ureters, at which point they are referred to as ureteral stones. Kidney and ureteral stones are also called urinary stones.

Kidney stones do not always need to be treated. Very small stones often move to the bladder, where they can be excreted in the urine within a few days or weeks. So when the stones are small, it is often enough to treat the symptoms with painkillers, drink plenty of water, and be active. With medium-sized stones, certain medications can help. They get the muscles of the lower urinary tract to relax, which helps in excreting them.

Larger stones usually have to be removed surgically or broken up using sound waves. They can move through the ureter or remain stuck in the outlet of the renal pelvis, causing severe pain and other discomforts. Which treatment is best depends on the size, type, and location of the stones in the kidneys or urinary passages.

Many people suffer from kidney or ureteral stones repeatedly throughout their life. To prevent this, it is important to identify the causes.

What are the symptoms of kidney stones?

Small urinary stones do not necessarily cause any symptoms. Sometimes the person affected feels a slight pulling in the kidney area, without suspecting a kidney stone. Others have no symptoms at all. The kidney stones are then often discovered by accident, when an X-ray or ultrasound image of the abdomen is taken. Some stones are also only noticed when they are passed with the urine.

Stones become noticeable when they block the outlet of the renal pelvis or move through the ureter – the main symptom is pain, which can range from mild discomfort to severe cramps. Where the sufferer feels the pain depends on where the stones are. Depending on which section of the ureter the stone is in at the particular moment, the pain may be felt in the abdomen, stomach or back.

The pain is particularly severe when a stone moves through one of the natural bottlenecks in the ureter. One such bottleneck, for example, is located where the ureters drain into the urinary bladder. Sudden, severe attacks of pain are then typically felt in the person’s side. They can radiate outwards to the abdomen and are known as renal colic. The pain can come in waves, growing stronger and weaker in turn. They are sometimes accompanied by a high temperature and headaches. Sufferers often tend to bend over and squirm to find a position in which they can better tolerate the pain. Renal colic can last between 20 and 60 minutes.

Other symptoms that a stone in the ureter can cause are:

- pain when passing water

- frequent or increased urinary urgency

- blood in the urine

- pain sometimes radiating to the genital organs

Why do kidney stones occur?

Kidney stones are essentially crystals that form when certain substances bind in the urine. They often consist of salts containing calcium, but they can also be made up of uric acid and other minerals:

- 80 percent of people with kidney stones have calcium stones

- 5 to 10 percent have uric acid stones

- 10 percent of kidney stones consist of the mineral struvite

Stones composed of other substances are rare.

These substances are usually dissolved in the urine. With some illnesses, however, the concentration of the substances in the urine is higher and it forms crystals. For example, with over-active parathyroid glands, there is an increase in the amount of calcium in the urine. With gout, meanwhile, there is an increase in the uric acid level. The excess is occasionally genetic, for example in the case of stones made up of the amino acid cysteine.

There are also substances such as citrate, which prevent the formation of stones. If their concentration in the urine is too low, it may lead to stones forming. A citrate deficiency can be caused by chronic diarrhea, for example.

Diet, too, can play a part. Some foods, such as rhubarb, contain a lot of oxalic acid. Other foods, such as liver, can cause an increase in the uric acid level. This can help stones form. When fluid intake is too low, the concentration of stone-forming substances also increases.

As well as the ratio of stone-forming to stone-preventing elements in the urine, the acidity of the urine is a key indicator – most types of stones occur due to urine being too acidic. Stones can also occur when acids are lost, for example due to a urinary tract infection.

Certain medications can also change the urine or form crystals themselves. This increases the risk that kidney stones will form.

Some people have abnormalities in the kidneys, for example kidney cysts or horseshoe kidney, which increases their risk of kidney stones. Horseshoe kidney is when the two kidneys have grown together at the lower ends.

How common are kidney stones?

Kidney stones are common: according to estimates in the United States, at least 10 percent of people have kidney or ureteral stones at some point in their life. In Germany, every year 1 to 2 percent of the population get them, men more frequently than women. Kidney and ureteral stones can occur at any age, including in children. Incidence is highest in people aged 40 to 60.

When is a kidney stone excreted?

How long it takes for a kidney stone to be excreted varies greatly. Small stones are often excreted with the urine after a week or two. If a stone does not wash out by itself within 4 weeks, it is usually treated.

Kidney stones usually only produce symptoms when they get into the ureter. The symptoms depend very much on their size:

- Most stones with a diameter of under 5 millimeters move, on their own, into the bladder and are excreted there.

- Half of all stones between 5 and 10 millimeters in size are also excreted by themselves.

- Stones with a diameter of over 10 millimeters usually need to be treated.

Important: In up to 50 percent of cases, stones form a second time or sometimes more within a period of 5 years. So it is important to take preventive measures.

If kidney stones are not treated, they can narrow or block the ureters. This increases the risk of infection; urine can become stagnant and put pressure on the kidneys. This does not happen often, however, as most kidney stones are treated before complications set in. Indications of an infection in the upper urinary tracts are a high temperature, shivering, pain in the side and the lower back, and nausea and vomiting.

How can kidney stones be prevented?

If the reason behind the kidney stones is not eliminated, they will recur regularly. The prevention of kidney stones depends on their composition and their cause. The stones are analyzed in a laboratory to determine these. For this reason, it is important to watch out for the stones when urinating and to collect them using a sieve or filter.

Depending on the cause, dietary changes may be useful, for example, less meat or salt. Medications can influence the pH value of urine or reduce the amount of calcium or uric acid in the urine. The preventive measures prescribed also depends on the person’s risk of more kidney stones.

Another preventive measure recommended by specialists is to drink plenty of fluids – at least two liters per day. The patient should discuss the ideal amount with their doctor.

For more detailed information about preventing kidney stones, go to gesundheitsinformation.de.

How are kidney stones diagnosed?

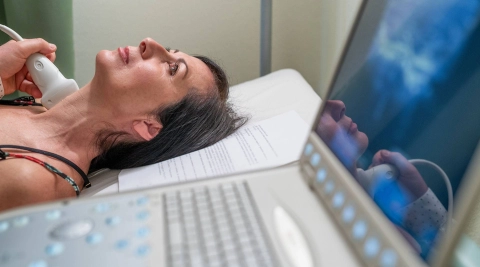

The classic kidney stone symptoms provide pointers towards an initial diagnosis. However, they are not always clear enough to show a definitive cause. An ultrasound scan, which makes most kidney and ureteral stones visible, will then help. Doctors will sometimes order a computed tomography (CT) scan to more accurately determine the size and location of the stone.

An x-ray image of the kidneys, ureters and bladder is less precise: calcium stones are easily identified, but struvite stones show up less well on x-rays, and uric acid stones not at all. However, x-rays can be useful in verifying the success of any treatment.

Blood and urine tests are also important. They can give indications of possible causes, such as an infection, or reveal high calcium or uric acid levels.

How are kidney stones treated?

Based on the size and location of the stones, a judgment can be made on whether they need to be treated or not. In the case of smaller kidney stones that are not causing any pain, the patient can wait until they are excreted on their own, with the urine. Until then, pain can be alleviated with painkillers such as diclofenac, ibuprofen, paracetamol and metamizol. Stronger products (opioids) are an option when the pain is very severe.

When ureteral stones are between 5 and 10 millimeters, an attempt will be made to use drugs to get the urinary tract muscles to relax, which helps excretion.

Larger stones need to be treated in most cases. Depending on their location and how large they are, they are broken down by ultrasound waves, using endoscopy, or removed via a small operation.

Further information

If you suspect kidney stones or you are experiencing symptoms like pain when passing water, you can consult your family doctor.

- Aboumarzouk OM, Jones P, Amer T et al. What Is the Role of alpha-Blockers for Medical Expulsive Therapy? Results From a Meta-analysis of 60 Randomized Trials and Over 9500 Patients. Urology 2018; 119: 5-16.

- Afshar K, Jafari S, Marks AJ et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and non-opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (6): CD006027.

- Amer T, Osman B, Johnstone A et al. Medical expulsive therapy for ureteric stones: Analysing the evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analysis of powered double-blinded randomised controlled trials. Arab J Urol 2017; 15(2): 83-93.

- Bao Y, Tu X, Wei Q. Water for preventing urinary stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; (2): CD004292.

- Campschroer T, Zhu X, Vernooij RW et al. Alpha-blockers as medical expulsive therapy for ureteral stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; (4): CD008509.

- Chou R, Wagner J, Ahmed AY et al. Treatments for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. (AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews; No. 61). 2020.

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Urologie (DGU), Arbeitskreis Harnsteine der Akademie der Deutschen Urologen. S2k-Leitlinie zur Diagnostik,Therapie und Metaphylaxe der Urolithiasis. AWMF-Registernr.: 043-025. 2018.

- Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158(7): 535-543.

- Garcia-Perdomo HA, Echeverria-Garcia F, Lopez H et al. Pharmacologic interventions to treat renal colic pain in acute stone episodes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog Urol 2017; 27(12): 654-665.

- Hollingsworth JM, Canales BK, Rogers MA et al. Alpha blockers for treatment of ureteric stones: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016; 355: i6112.

- Miller NL, Lingeman JE. Management of kidney stones. BMJ 2007; 334(7591): 468-472.

- Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet 2006; 367(9507): 333-344.

- Oestreich MC, Vernooij RW, Sathianathen NJ et al. Alpha-blockers after shock wave lithotripsy for renal or ureteral stones in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; (11): CD013393.

- Phillips R, Hanchanale VS, Myatt A et al. Citrate salts for preventing and treating calcium containing kidney stones in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (10): CD010057.

- Tseng TY, Preminger GM. Kidney stones: flexible ureteroscopy. BMJ Clin Evid 2015: pii: 2003.

In cooperation with the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen) (IQWiG).

As at: